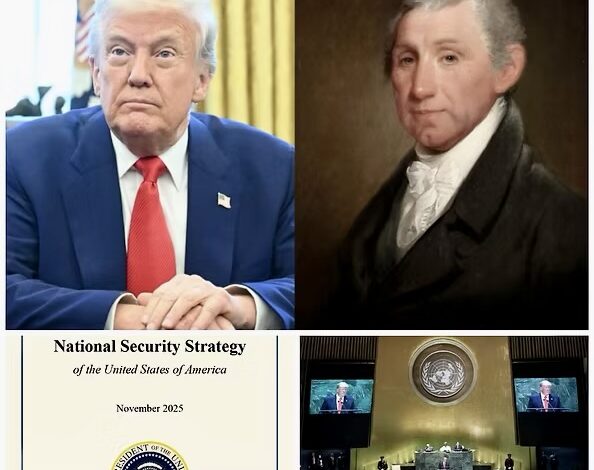

A National Security Strategy Caught Between America First and a Multilateral World

By Ahmed Fathi

American Television News

“Clear Voices. Global Impact”

News & Media Production

UNHQ, New York: The 2025 National Security Strategy is not a policy document. It is a worldview—sharpened, fortified, and aimed squarely at the post–World War II order the United States once championed. Reading it from inside the United Nations, where multilateralism is oxygen, feels like watching the architect of a house return decades later with a bulldozer and a tape measure, determined to “fix” what everyone else has learned to live in.

The national security strategy’s opening salvo rejects 30 years of American foreign policy as indulgent, misguided, and captured by globalists who outsourced sovereignty to “transnational institutions.” (p.1–2) Let’s call this what it is: a direct ideological attack on the very foundations of cooperative global governance.

Where the UN sees shared responsibility, the NSS sees dilution of purpose. Where the UN sees interdependence, the NSS sees vulnerability. Where the UN sees diplomacy, the NSS sees interference.

This is not a disagreement in tone—it is a rupture in philosophy.

Migration: The UN’s Humanitarian Pillar Meets America’s New Fortress

The most jarring collision with multilateralism is the document’s absolutist stance on migration. “The era of mass migration is over,” it declares, placing border control above almost every other national security priority (p.11).

This is the antithesis of the UN’s approach:

-

UNHCR frames displacement through protection and rights.

-

IOM treats migration as a global system requiring shared solutions.

-

The Global Compact on Migration assumes cooperation, not unilateral walls.

But the NSS frames migration as a strategic threat—as destabilizing as terrorism or fentanyl. To put it bluntly, the document treats vulnerable human beings as vectors of insecurity rather than stakeholders in global stability.

This single shift will reverberate through every humanitarian negotiation for years.

The Monroe Doctrine Resurrected—Now With Teeth

Then comes the Western Hemisphere section—a geopolitical plot twist so sweeping it should come with its own sirens.

The NSS introduces a “Trump Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine,” warning all foreign powers to keep their hands off anything—from ports to minerals to data cables—south of Texas (p.15–18).

This isn’t subtle. It’s not even polite.

It is Washington saying: “This hemisphere is ours. Full stop.”

For the UN, this is more than uncomfortable—it is structurally incompatible. The entire multilateral order is built to prevent great powers from treating regions as private property. Yet the corollary does exactly that, turning the Western Hemisphere into a strategic enclosure.

Latin American states may publicly welcome investment, but in UN corridors they will privately ask:

If the United States claims sovereign veto power over our partnerships, where does our sovereignty begin?

This doctrine sidelines:

-

UN development programs

-

regional organizations

-

multilateral financing

-

foreign partnerships not stamped with Washington’s approval

In effect, it reduces multilateralism to a cameo role in America’s backyard.

Europe: A Civilization Diagnosed, Not Engaged

The NSS’s treatment of Europe uses language more reminiscent of cultural essayists than strategic planners. Europe, it says, is facing “civilizational erasure,” demographic collapse, loss of identity, and regulatory suffocation (p.25–27).

That is not analysis. That is an obituary.

This approach undermines the UN’s ability to maintain a unified Western diplomatic front—something essential in Security Council dynamics, sanctions regimes, and humanitarian resolutions. If Washington sees Brussels as a problem rather than a partner, the cohesion that has sustained the liberal order since 1945 begins to crack.

China: The Multilateral System’s Stress Test

If one country haunts the document, it is China. The NSS casts Beijing as the singular adversary shaping every strategic domain: supply chains, AI, rare minerals, intellectual property, migration, propaganda, even pharmaceuticals (p.20–24).

This is not competition. It is systemic confrontation.

But here lies an immovable fact: The UN cannot function without China. It is the second-largest funder, a permanent Security Council member, a major contributor to peacekeeping, and a critical player in global health, climate negotiations, and development financing.

When the United States frames China as an existential threat across every domain, multilateralism becomes collateral damage. The risk is simple: two competing global systems beginning to form, neither fully compatible with the UN’s universal model.

The Middle East: A Rare, Fragile Convergence

In one surprising turn, the NSS’s vision for the Middle East partially aligns with UN priorities—de-escalation, stability, hostage release, avoiding regional war, and supporting new diplomatic arrangements (p.27–29).

But the motivations diverge sharply. The UN seeks sustainable peace grounded in rights, governance, and humanitarian law. The NSS seeks a stabilized environment that reduces American burdens and contains adversaries.

This convergence is useful—but fragile. The next flare-up in Gaza, Lebanon, Syria, or the Red Sea could easily expose the ideological differences again.

Africa: Partnership or Resource Hunt?

Africa is framed as an investment frontier, with minerals and energy at the center of U.S. interests (p.29).

African leaders may welcome competition for resources—China, Russia, Turkey, the EU, and the Gulf states are already there—but the UN’s vision for Africa is broader:

-

governance

-

human development

-

peacebuilding

-

industrialization

-

sustainable growth

The NSS focuses sharply on what Africa has, not what Africa seeks to become. That imbalance is where multilateral organizations must step in.

The Bottom Line: Collision Is Coming—But Opportunity Isn’t Dead

The NSS is the most sovereignty-first, multilateralism-skeptical American strategy in the UN era. It questions the premise of global cooperation and treats the world as a competitive map rather than a shared system.

But even a unilateralist America cannot outrun global realities:

-

pandemics

-

climate impacts

-

supply chain fragility

-

technological governance

-

cross-border crises

These are problems no nation—however powerful—can solve alone.

So yes, collision is inevitable. But collapse is not.

The UN and the multilateral system must now work with the cracks, exploit the openings, and remind Washington of a truth written into every chapter of modern history:

A world led by one nation’s will is unstable. A world led by shared responsibility is sustainable.

And in the end, even America will rediscover that it cannot build a fortress tall enough to replace the value of a functioning international system